2. Havitz, M. E., Zemper, E. D., & Snelgrove, R. (2010, May). Detailed Vision: Lauren P. Brown and the NCAA Cross Country Championships. Presented at the 2010 North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) convention, Walt Disney World, FL.

2. Havitz, M. E., Zemper, E. D., & Snelgrove, R. (2010, May). Detailed Vision: Lauren P. Brown and the NCAA Cross Country Championships. Presented at the 2010 North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) convention, Walt Disney World, FL.MSU Cross Country Study

Supported by

University of Waterloo

MSU Track and Field Alumni Association, The Finish Line Club

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

1. Havitz, M. E. (2009, October). Lifelong Longitudinal Retrospectives on Ego Involvement and Commitment with Running. Presented at the Sport Canada Research Initiative (SCRI) Conference, Ottawa, ON.

Abstract: This research will employ a retrospective approach to sport and recreation participation over extended periods of time. It will examine processes by which, and conditions in which, competitive young adult runners develop and maintain (or not) ego involvement with activity and commitment to ancillary programs, services and products. These processes and conditions, though important to a broader understanding of adherence to physical activity participation, are rarely explored longitudinally. Extant research on these topics is predominantly cross-sectional and most has explored antecedents of ego involvement and commitment with little attention to maintenance and ebb and flow of participation over adult life spans. Approximately 300 people, all elite to relatively elite runners in their early 20s, but who currently range in age from 21 to 90, will access a photo elicitation-based survey (on-line or hard copy). It explores via short answer questions, issues related how and when they first defined themselves as runners, social group contexts related to team affiliations, highs and lows associated with running, attachment to training and competitive settings (e.g., routes, courses and races), and attachment to brands (e.g., shoes and gear). Close-ended standardized scales measure ego involvement, hedonic, and eudaimonic well-being at the activity level over each decade of their lives, as well as general health and well-being in their early 20s and at present. A modified questionnaire will be sent to a similarly sized snowball sample of less elite runners, identified by participants in the first group. Follow-up interviews will be conducted with select individuals from both groups. Better understanding of loyalty may facilitate social and political goals by enhancing citizens' quality of life, developing community, and increasing participation rates. It may also assist recreation and sport organizations increase revenues and generate positive reputations. High levels of involvement and loyalty may bring personal benefits in the form of improved skills, health, quality of life, and social benefits such as satisfying social relationships and more defined social identities. The research is also designed to understand why some people are not loyal and may provide structures and opportunities for eliminating or reducing constraints that negatively impact development of loyalty. Finally, it will assess negative consequences of leisure and sport loyalty including deteriorating family relationships and friendship networks, dysfunctional social worlds; and negative health outcomes including body image issues and injury.

2. Havitz, M. E., Zemper, E. D., & Snelgrove, R. (2010, May). Detailed Vision: Lauren P. Brown and the NCAA Cross Country Championships. Presented at the 2010 North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) convention, Walt Disney World, FL.

2. Havitz, M. E., Zemper, E. D., & Snelgrove, R. (2010, May). Detailed Vision: Lauren P. Brown and the NCAA Cross Country Championships. Presented at the 2010 North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) convention, Walt Disney World, FL.

Abstract: Though the world was gripped in unprecedented economic depression and on the brink of a second catastrophic war, the National Collegiate Athletic Association made significant strides in the 1930s. During this decade the NCAA added four new team championships (swimming, gymnastics, cross country, and basketball) more than doubling the extant number of official championships (golf, outdoor track and field, and wrestling). The inaugural NCAA Cross Country championship stepped off near the banks of the Red Cedar River on the campus of Michigan State College on November 21, 1938. The intent of this research is to explore the contributions of a visionary in a formative era of intercollegiate cross country; a sport that is simultaneously at the center and periphery of the college athletic spectrum, and which is paradoxically the most integrated sport within the spatial milieu of college campuses while being perhaps the least spectator friendly. The visionary who brought this championship to fruition and nurtured it during its formative years, Lauren Pringle Brown, was a decorated runner for Michigan State from 1926-1930 before assuming cross country coaching duties for his alma mater in 1931. Coach Brown produced top caliber cross country and track and field teams during his 16 year coaching career. Most notable with respect to cross country were his charges' five straight IC4A Championships earned at New York's Van Cortland Park from 1933 to 1937. This meet represented, at least for the eastern United States, the de-facto national championship prior to inception of the NCAA meet, and lent an air of credibility to the fledgling championship's chosen venue. Brown played a leading role in the National Collegiate Cross Country Coaches Association, including long service as Secretary and as member of the Executive Committee, and has been credited with developing the initial scoring system used in NCAA cross country championships. His service spanned the entire 26 year history of that event's "run" on the Michigan State campus. He designed and repeatedly modified the course in order to accommodate an authentic cross country experience in the midst of Michigan State's burgeoning physical plant as it evolved from a small agricultural and applied sciences school to, by his retirement, a world-class university enrolling over 40,000 students. Brown's coaching and voluntary service record accrued on a part-time basis while devoting full-time service as director of Michigan State's University Printing office. Meticulous in all aspects of life, "Brownie" left extensive archival records to Michigan State University and the NCAA, including minutes of the aforementioned Coaches Association meetings, NCAA championship programs, roster and photo records of his teams and some major competitions, numerous aerial photos depicting the Great Depression-era Michigan State College campus, with particular focus on the route traversed by the original NCAA cross country course and subsequent early competitions, and detailed hand-edited maps of those courses. Structured survey data and semi-structured interview data collected from surviving members of Lauren Brown's cross country teams, men now in their 80s and 90s, have been collected to supplement the aforementioned written records and provide additional perspective on the life, times, and passions of a unique and complex individual. Together, these visual archives and personal recollections contribute to a fascinating narrative of a man central in instigating and firmly establishing cross country as a viable NCAA competition.

A full version of this paper has now been published:

Havitz, M. E., & Zemper, E. D. (2013). “Worked out in infinite detail”: Michigan State’s Lauren P. Brown and the nationalization of intercollegiate cross country. Michigan Historical Review, 39, 1-39.

Please contact Mark Havitz at mhavitz@uwaterloo.ca to request a copy of this paper.

At left: Lauren P. "Brownie" Brown

(MSU Archives & Historic Collections)

Founder of the NCAA Cross Country Championships

3. Snelgrove, R., & Havitz, M. E. (2009, May). The retrospective method in sport management research: Potential and pitfalls. Presented at the NASSM 2009 Conference, Columbia, SC.

Abstract: The study of psychological constructs, such as motivation or ego involvement, is a common approach taken by researchers seeking to understand engagement in sport activities (e.g., Beard & Ragheb, 1983; Funk, Ridinger, & Moorman, 2004; Havitz & Dimanche, 1999; McDonald, Milne, & Hong, 2002). These psychological variables have also been studied as ways of explaining commitment and behavioral loyalty to a sport activity or recreational agency (e.g., Funk & James, 2001; Gladden & Funk, 2002; Iwasaki & Havitz, 2004; Kyle, Graefe, Manning, and Bacon, 2004; Kyle & Mowen, 2005). However, in most instances research has been conducted on a cross-sectional basis. A notable exception is the work of Havitz and Howard (1995) that examined the stability of ego involvement in three leisure activities (golf, downhill skiing, windsurfing) over the period of a year. They collected data at three distinct points in time (i.e., in-season, off season, preseason) and found evidence that most facets of involvement remained stable, while others did not. Questions remain, however, with respect to how enduring some of these constructs really are over extended periods of time. Specifically, we know little about the genesis of ego involvement in individuals (Funk et al., 2004), the extent to which it fluctuates (up and down) over the course of life spans, what happens to ego involvement levels among people who have disengaged from active participation in a particular activity or sport, and what are the effects of ancilliary situational contexts (coaching, spectating, etc.) on ego involvement levels (Naylor & Havitz, 2007). An approach to gaining insight into these issues would be through the use of longitudinal research. It has been suggested that longitudinal research provides a more complete approach to empirical research (Ruspini, 1999). There are essentially two forms of longitudinal research - prospective and retrospective. The prospective design is widely regarded as the preferred approach, because of its ability to collect data that is contemporaneous and therefore more valid, rather than data which is based on memory (Henry et al., 1994; Yarrow et al., 1970). Henry et al noted that retrospective errors can occur because people (a) forget past events, (b) are unable to accurately recall dates, and (c) reconstruct the past to fit with their current situation. They concluded that "their results failed to find substantial evidence of the validity (in the form of agreement with prospective measures) of retrospective measures of subjective psychological states and family processes" (p. 99). Their finding is generally consistent with work by Jaspers et al. (2008) that compared contemporaneous and retrospective data on attitudes; however, some noteworthy exceptions exist. However, a prospective longitudinal approach may be undesirable for a number of reasons including the time it takes to complete the research project, cost, and significant participant drop out (Hardt & Rutter, 2004). Also, a long-term longitudinal approach may not be possible in certain cases, such as those involving older adults. Although the consensus in the literature is that the retrospective method does not produce similar objective results as obtained through the prospective method, there is an important benefit that must be noted. The retrospective approach results in a useful way of capturing the subjective interpretations of the past from the perspective of the person who lived those experiences. Although the exact path or causality of experiences may not be captured, the relative importance of their interpretations to current psychological states would be obtained (Henry et al., 1994; Yarrow et al., 1970). As our past or narrative identity, is an important part of who we are (McAdams, 1985), the current subjective interpretations of the past may be more important than objective assessments. To the extent that people make decisions about the future based on the past, the subjective measure of a construct on a retrospective basis would be much more important for the researcher to understand. In addition, we will explore avenues for increasing the reliability of retrospective approaches. For example, photo elicitation techniques have an established history in leisure research (Stewart & Floyd, 2004) and Samuels (2007) outlined numerous benefits to using photo elicitation in research contexts. In summary, the purpose of this paper will be to highlight the critiques of the retrospective method to date, and the potential for its use in sport management research. In light of a research project's objectives, specific strategies will be suggested to overcome potential weaknesses in a retrospective design.

4. Snelgrove, R., & Havitz, M. E. (2010). Looking back in time: The pitfalls and potential of retrospective methods in leisure studies . Leisure Sciences, 32, 337-351 .

Abstract: An increased focus on alternate theoretical perspectives, methodologies, and methods is needed in leisure studies. Although retrospective methods have been employed in a range of disciplines, criticism has been leveled at their validity, reliability, and trustworthiness. Possibilities and critiques of retrospective methods are discussed as either attempts at controlling or interpreting the past. Techniques for minimizing post-positivist concerns include stimulating memories using cues such as photos, allowing participants to report freely rather than forcing responses, and studying salient phenomenon that are subject to accurate recall. Interpretive methods such as narrative inquiry, autoethnography, and collective memory-work are also discussed and debated.

Full Text -- This paper is copyrighted, but a personal copy can be obtained by contacting Mark Havitz at mhavitz@uwaterloo.ca

5. Havitz, M. E., & Snelgrove, R. (2010, October). Epiphanies and Processes: Retrospective Descriptions of Initial Ego Involvement with Running. Presented at the Sport Canada Research Initiative (SCRI) Conference, Ottawa, ON.

Abstract: Three months into an anticipated 12-15 month data collection period, this abstract is based on initial coding of open-ended survey responses from 36 former competitive distance runners. This sub-sample is drawn from an estimated complete sample of approximately 400. The complexities involved in locating and communicating with members of the desired population has resulted in the survey being released in waves. As the study population ranges in age from early to late adulthood, initial focus has been on runners over 70 years of age. People are passionate about this topic and survey response rates for the first wave of the study currently stands at over 75 percent with some promised surveys still in process. Consistent with the length of the questionnaire, which includes over 20 pages of open-ended and quantitative response questions, survey completion times have ranged from 45 minutes to over six hours. Outright refusals account for less than five percent of the population to date. The primary questions of interest here are the initial motivations and nature of people’s experiences when participating in an activity for the first time. Specifically, the questionnaire posed the questions: (a) “When did you become, in your mind, a runner?” and (b) “Thinking back to before college, what motivated you to run?” Given the fluid nature of data collection, the qualitative nature of the data in question, and the relatively small sample upon which this discussion is based, we will avoid speaking to specific percentages. Respondents began running between the ages of 6 and 20, nearly all in organized track and field or cross country contexts. Both positive and negative motives played roles for various respondents, though usually independently in the sense that few reported both positive and negative themes. Positive motives included emulation of significant others and enjoyment derived from participation, whereas negative motives included variations on coercion, punishment, or fear. Major emergent themes that explain continuance in running after initial experiences include experiencing early competitive success and body image comfort. The time frame in which respondents self-identified as “a runner” varied considerably. A plurality identified a specific episode (e.g., the 16th lap of a 2 mile training run with cousins and friends), date (e.g., November 4, 1944) or meaningful time (e.g., a 5:02 mile at age 13). These instances are typically described in lucid detail even though all first wave respondents initially ran sometime prior to 1970. Another large group described their identification as runners in terms of an evolutionary process, most often spanning several weeks or months, but occasionally taking several years. Further, there is strong evidence that most respondents, including those who no longer train, continue to self-identify as runners. For example, one 88 year-old noted that “I still run in my dreams” prior to providing detailed descriptions of both his dreams and the real-life contexts from the 1940s in which his dreams are often set. Preliminary conclusions are that self- identity may have multiple origins, but additional analyses are needed to determine which, if any, of the origins are most affiliated with long term self-identity. Self-identity as a runner, in particular, may have important consequences for continued involvement in the sport (e.g., participant, coach, volunteer, spectator) as well as influencing others to run or become involved in the sport. Both qualitative and quantitative data have been collected to aid in answering these questions, but have not yet been integrated into the present analyses.

6. Havitz, M. E., & Geelhoed, B. (2011, May) “Hurry Back!” Insider Perspectives on Karl A. Schlademan’s Post-WWII Cross Country Coaching Dynasty. Presented at the 2011 North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) convention, Austin, TX.

Abstract draft: Though fought largely in killing fields of Europe, jungles of Southeast Asia, and Pacific beaches, the Second World War had profound effect on most aspects of North American society. This impact was especially evident at Land Grant colleges where government mandated two years of military drill among male students made them fertile ground for recruiting relatively mature and seasoned junior officers. One consequence was that male dominated intercollegiate athletics literally shut down at schools like Michigan State and the pioneer Land Grant school’s teams, including cross country which dominated eastern landscapes in the 1930s, were slow to recover. Following the 1946 season, Coach Lauren P. Brown stepped aside in deference to a burgeoning workload at the campus mimeograph shop and perhaps coaching burnout and post-war angst. His successor, Hall of Fame track and field coach Karl A. Schlademan (1890-1980) enjoyed a stellar career spanning five decades from before World War I to the close of the 1950s. The DePauw University graduate left legacies at the University of Kansas, Washington State and Michigan State. In some respects Schlademan’s career was typical of an era when coaching was less specialized and men often were assigned to multiple sports. Indeed, Schlademan briefly served as basketball coach at Kansas prior to turning the reigns back to Phog Allen in 1919 and well into the late 1940s, he still juggled multiple duties. Schlademan served on Charlie Bachman’s Michigan State football staff while holding down primary responsibilities for track and field and later cross country. Although the latest addition to his coaching repertoire, Schlademan enjoyed immense success in cross country, garnering an impressive five NCAA team championships, four IC4A championships, six Big Ten titles (MSC joined conference competition in 1950) and a number of runner-up finishes during his eleven-year tenure from 1947 through 1957. He also maintained a historic and competitive dual meet series with eastern power Penn State. In contrast to extensive materials left to Michigan State by his predecessor Brown, Schlademan was less inclined to retain memorabilia and left the university no archival collection. However, Schlademan’s intercollegiate athletic role was significant and ample secondary data exist. In addition to extant National Cross Country Coaches Association archives available from the NCAA, national publications including the Track and Field News and New York Times; local newspaper accounts in the State News and Lansing State Journal; and Michigan State’s yearbook (Wolverine) contain information on Schlademan and his teams. Several books, including John Hannah’s A Memoir and David Thomas’ MSC: John Hannah and the Creation of a World University add broader context and speak directly to Schlademan’s contributions. With respect to primary source material, we have interviewed his son Dr. Karl R. Schlademan and surveyed over 30 of his MSC/MSU runners, including the majority of his star athletes – numerous Big Ten and NCAA champions, All-Americans, and Olympians – as well as a number of lesser runners who provide depth of perspective and evidence of his coaching techniques from their personal archives. Data suggest that Schlademan was a sophisticated and opportunistic international recruiter for his time, a man of relatively few well-placed words including an effective two-word inspirational pre-race speech to his 1949 NCAA champions, inspiration for numerous nicknames related to his personality and gravelly voice, and had a penchant for protecting the physical and mental health of his star pupils sometimes at the expense of other athletes. Together, archival materials and personal recollections contribute to a fascinating narrative of a man central in nurturing and expanding NCAA cross country competition in the post-World War era.

Abstract draft: Though fought largely in killing fields of Europe, jungles of Southeast Asia, and Pacific beaches, the Second World War had profound effect on most aspects of North American society. This impact was especially evident at Land Grant colleges where government mandated two years of military drill among male students made them fertile ground for recruiting relatively mature and seasoned junior officers. One consequence was that male dominated intercollegiate athletics literally shut down at schools like Michigan State and the pioneer Land Grant school’s teams, including cross country which dominated eastern landscapes in the 1930s, were slow to recover. Following the 1946 season, Coach Lauren P. Brown stepped aside in deference to a burgeoning workload at the campus mimeograph shop and perhaps coaching burnout and post-war angst. His successor, Hall of Fame track and field coach Karl A. Schlademan (1890-1980) enjoyed a stellar career spanning five decades from before World War I to the close of the 1950s. The DePauw University graduate left legacies at the University of Kansas, Washington State and Michigan State. In some respects Schlademan’s career was typical of an era when coaching was less specialized and men often were assigned to multiple sports. Indeed, Schlademan briefly served as basketball coach at Kansas prior to turning the reigns back to Phog Allen in 1919 and well into the late 1940s, he still juggled multiple duties. Schlademan served on Charlie Bachman’s Michigan State football staff while holding down primary responsibilities for track and field and later cross country. Although the latest addition to his coaching repertoire, Schlademan enjoyed immense success in cross country, garnering an impressive five NCAA team championships, four IC4A championships, six Big Ten titles (MSC joined conference competition in 1950) and a number of runner-up finishes during his eleven-year tenure from 1947 through 1957. He also maintained a historic and competitive dual meet series with eastern power Penn State. In contrast to extensive materials left to Michigan State by his predecessor Brown, Schlademan was less inclined to retain memorabilia and left the university no archival collection. However, Schlademan’s intercollegiate athletic role was significant and ample secondary data exist. In addition to extant National Cross Country Coaches Association archives available from the NCAA, national publications including the Track and Field News and New York Times; local newspaper accounts in the State News and Lansing State Journal; and Michigan State’s yearbook (Wolverine) contain information on Schlademan and his teams. Several books, including John Hannah’s A Memoir and David Thomas’ MSC: John Hannah and the Creation of a World University add broader context and speak directly to Schlademan’s contributions. With respect to primary source material, we have interviewed his son Dr. Karl R. Schlademan and surveyed over 30 of his MSC/MSU runners, including the majority of his star athletes – numerous Big Ten and NCAA champions, All-Americans, and Olympians – as well as a number of lesser runners who provide depth of perspective and evidence of his coaching techniques from their personal archives. Data suggest that Schlademan was a sophisticated and opportunistic international recruiter for his time, a man of relatively few well-placed words including an effective two-word inspirational pre-race speech to his 1949 NCAA champions, inspiration for numerous nicknames related to his personality and gravelly voice, and had a penchant for protecting the physical and mental health of his star pupils sometimes at the expense of other athletes. Together, archival materials and personal recollections contribute to a fascinating narrative of a man central in nurturing and expanding NCAA cross country competition in the post-World War era.

Full paper currently in development. A personal draft copy can be obtained by contacting Mark Havitz at mhavitz@uwaterloo.ca

Karl "Schnarly/Grumbles" Schlademan photo courtesy of MSU Archives & Historic Collections.

Schlademan's Spartans won five NCAA Cross Country Titles in his eleven years as head coach..

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

7. Havitz, M. E., & Snelgrove, R. (2011, June). An Application of Retrospective Methods to the Study of Involvement with Running. Presented at the North American Society fo Sport Management NASSM 2011 Conference, London, ON.

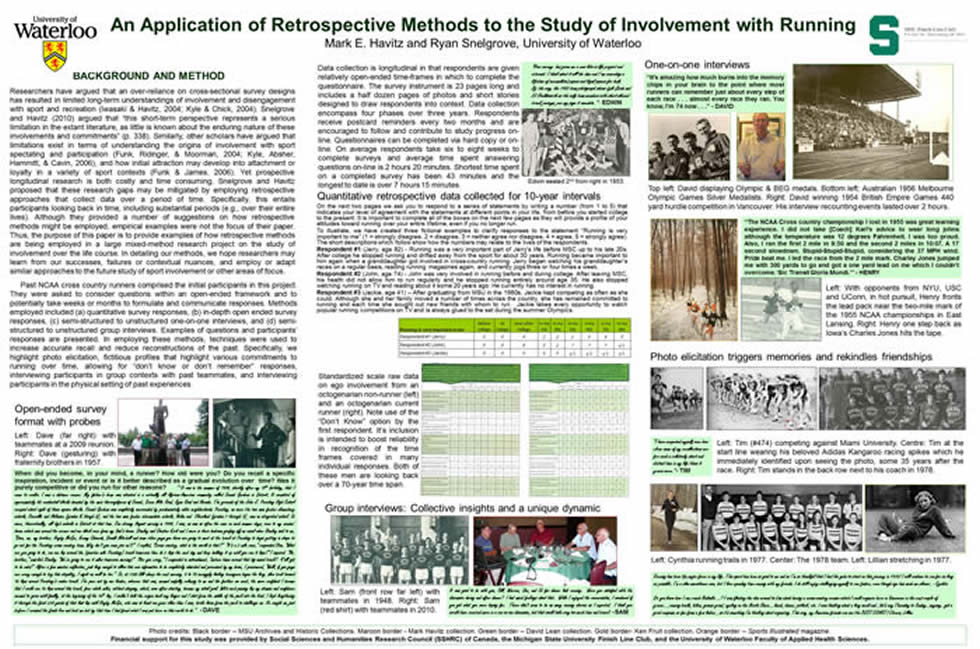

Abstract draft: Researchers have argued that an over-reliance on cross-sectional survey designs has resulted in limited long-term understandings of involvement and disengagement with sport and recreation (Iwasaki & Havitz, 2004; Kyle & Chick, 2004). Snelgrove and Havitz (2010) argued that “this short-term perspective represents a serious limitation in the extant literature, as little is known about the enduring nature of these involvements and commitments” (p. 338). Similarly, other scholars have argued that limitations exist in terms of understanding the origins of involvement with sport spectating and participation (Funk, Ridinger, & Moorman, 2004; Kyle, Absher, Hammitt, & Cavin, 2006), and how initial attraction may develop into attachment or loyalty in a variety of sport contexts (Funk & James, 2006).

Snelgrove and Havitz proposed that these research gaps may be overcome, in part, by employing retrospective approaches that collect data over a period of time. Specifically, this entails participants looking back in time, including substantial periods (e.g., over their entire lives). Although they provided a number of suggestions on how retrospective methods might be employed, empirical examples were not the focus of their paper. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to provide examples of how retrospective methods were employed in a large mixed-method research project on the study of involvement over the life course. Past NCAA cross country runners were participants in this project. In detailing our methods, it is hoped that researchers will be able to learn from our successes, failures or contextual nuances, and employ or adapt similar approaches to the future study of sport involvement or other areas of focus. Methods employed include (a) quantitative survey responses, (b) in-depth open ended survey responses, (c) semi-structured to unstructured one-on-one interviews, and (d) semi-structured to unstructured group interviews. Examples of questions and participants’ responses will be presented. In employing these methods, techniques were used to increase accurate recall and reduce reconstructions of the past. Specifically, we will discuss the use of techniques such as photo elicitation, fictitious profiles that highlight various commitments to running over time, allowing for “don’t know or don’t remember” responses, interviewing participants in group contexts with past teammates, and interviewing participants in the physical setting of past experiences. Research suggests that people are more accurate in their recall of past events when the subject is tied to their identities (Bluck & Habermas, 2000; Ross, 1989). As running was an important part of our participants’ lives, it is not surprising that responses were often detailed. As one 74 year-old man said, “It’s amazing how much burns into the memory chips in your brain to the point where most runners can remember just about every step of each race . . . almost every race they ran.” Participants who have since stopped running were also part of the study. An 88 year-old man explained his connection to running by stating, “I still run in my dreams” and backed that statement with lucid detail related to context and outcomes. Another 71 year-old respondent wrote after viewing some project prompts, “Thank you so very much for sending the pictures. Oh what memories they retrieve from the depths of my being!” Although memory concerns were an important consideration throughout data collection, other unanticipated challenges and opportunities arose such as participants’ deference to elite runners as gatekeepers of memories, and issues related to representing experiences of deceased runners through recollections and words of friends and family.

8. Snelgrove, R., & Havitz, M. E. (2011, June). "I am a Runner": Early Motivators and the Development of Sport Identities Presented at the NASSM 2011 Conference, London, ON.

Abstract draft: The presence of sport identities may have important consequences for understanding sport behaviors. Research has shown that people with sport identities are more likely to be loyal to an activity, sport organization or sport event, or consume related services or products than those who do not possess sport identities (Green, 2001; Iwasaki & Havitz, 2004; Kyle, Kerstetter & Guadagnolo, 2004; Laverie & Arnett, 2000; Trail, Anderson, & Fink, 2005). Although the connection between identity and behavior has been well established, the origins of those identities have been under-researched. Some research exists that seeks to understand the antecedents of sport identities, and related constructs, through cross-sectional survey designs (e.g., Funk, Ridinger, & Moorman, 2004; Kyle, Absher, Hammitt, & Cavin, 2006). However, these approaches are limited in that they do not fully capture the dynamics of identity development because they correlate current motives with existing identities. Motivations to initially engage in an activity may indeed proceed the development of identities (e.g., Funk & James, 2001, 2006), but present motivations may have little resemblance to earlier ones. Thus, there is a need to examine the development of identities in a longitudinal manner. Building on Snelgrove and Havitz’s (2010) suggestion, the present study explores, from a retrospective perspective, initial motivations and experiences when participating in long distance running to the development of a runner identity. Funk and James’ (2006) Psychological Continuum Model which emphasizes the processual aspects of identity development serves as the theoretical framework for this study. Method. Data were collected via open-ended survey responses from 60 competitive distance runners associated with a historically successful cross country program at a large Midwestern university. They represent the first wave of 75 potential participants from an estimated population of 600 living program alumni. The majority of first wave respondents were members of NCAA and/or conference champion teams though, at an individual level, competitive success levels varied widely. Respondents currently range in age from 21 to 90 but the majority are over age 60 as the first wave of data collection focused primarily on older runners. Consistent with the length of the questionnaire, which included both open-ended and quantitative response questions, survey completion times ranged from 45 minutes to over six hours. Both on-line and hard copy versions were made available and the data collection timeline was relatively open-ended affording adequate time to reflect retrospectively on experiences. Techniques suggested by Snelgrove and Havitz (2010) were employed to increase accurate recall and reduce reconstructions of the past. Outright refusals account for less than five percent of contacted first wave respondents. The two questions most salient to this paper include: (a) “Thinking back to before college, what motivated you to run?” and (b) “When did you become, in your mind, a runner?” Data were analysed using constant comparison methods in order to construct overarching themes that described running experiences early in their careers. Findings and Discussion. Respondents began running between the ages of 6 and 20, nearly all in organized track and field or cross country contexts. Both positive and negative motives played roles for various respondents, though usually independently in the sense that few reported both positive and negative themes. Positive motives included emulation of significant others and enjoyment derived from participation, whereas negative motives included variations on coercion, punishment, or fear. Whereas positive motives mirror those in sport and leisure motivation studies more broadly (McDonald, Milne, & Hong, 2002), negative motives have not been adequately addressed in the literature. Two major emergent themes explain early continuance in running after initial experiences: experiencing early competitive success and body image comfort. Early success as a motivator is consistent with research on the power of emotions and self-efficacy in sport continuance (Adler & Adler, 1998; Lee & Bobko, 1994). Although extant research addresses the constraining aspects of body type and body image comfort (Frederick & Shaw, 1995), respondents in this study suggested that body issues may also be viewed as an affordance. That is, participants who had limited success in other sports often found a connection with running. This finding is consistent with research suggesting that adolescents are drawn to activities consistent with self-image (Haggard & Williams, 1992; Kivel & Kleiber, 2000; Shaw, Kleiber & Caldwell, 1995). The time frame in which respondents self-identified as “a runner” varied considerably. A plurality identified a specific episode (e.g., the 16th lap of a 4 mile training run with cousins and friends), date (e.g., November 4, 1944) or meaningful time (e.g., a 5:02 mile at age 13). These instances are typically described in lucid detail even though all first wave respondents initially ran sometime prior to 1970. Another group described their identification as runners in terms of an evolutionary process, most often spanning several weeks or months, but occasionally taking several years. Further, there is strong evidence that most respondents, including those who no longer train, continue to self-identify as runners. In sum, the data suggest that the development of sport identities may have multiple origins and develop in various ways.

9. Havitz, M. E., & Wilson, A. W. (2011, November). Quantifying Lifetime Ego Involvement with Running. Presented at the Sport Canada Research Initiative (SCRI) Conference, Ottawa, ON.

Abstract draft: This research, as part of a larger program on ego involvement, psychological commitment and behavioural loyalty relationships in leisure contexts, will employ a retrospective approach to understand sport and recreation participation over extended periods of time. More specifically, the purpose is to examine processes by which, and conditions in which, runners develop and maintain (or not) involvement with the activity and commitment to the activity itself as well as ancillary programs, services and products over their individual life courses. These processes and conditions, though important to a broader understanding of adherence to physical activity participation, have only been tentatively explored longitudinally in past research. The theoretical basis of this project is a conceptual model of leisure involvement and loyalty which integrates social psychology and consumer behaviour literature with leisure literature in the areas of ego involvement, psychological commitment, and loyalty (Iwasaki & Havitz, 1999, 2004). The model posits that loyal participants go through progressive processes including: formation of high levels of ego involvement with leisure and sport activity; development of psychological commitment to the activity and various products, events, organizations and service providers; and resistance to change preferences toward products, events, organizations and service providers. Also, the model suggests that personal characteristics (e.g., skill, motivation, personality) and social-situational factors (e.g., social support, life-stage, social norms) influence processes leading to loyalty. As formal data collection is ongoing at present, the intent at this conference will be to present preliminary data collected from 125 participants for the purpose of examining the main path in the model, specifically those variables highlighted in bold. Data have been collected on a decade-by-decade basis, in order to facilitate examination of these processes over runners’ entire life spans.

10. Havitz, M. E. (June, 2012). Running with the tide and against the wind: Michigan State’s foundational 1974-1981 women’s cross country teams. Presented at the North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) 2012 Conference, Berkeley, CA.

Abstract draft: Michigan State University dominated eastern, Midwestern, and national cross country landscapes for a forty-year period spanning the 1930s through the early 1970s. During this era, MSU earned fifteen IC4A cross country titles against eastern competition, fourteen Big Ten titles in 22 years after joining the league in 1950, and eight NCAA team championships. In addition to its prominent position in hill and dale competition, the school played a formative role in developing the sport on a national scale, first by challenging eastern hegemony on its primary proving grounds in New York’s Van Cortlandt Park and then by uniting the nation’s college teams with a centrally based competition. Michigan State founded, nurtured and hosted the NCAA meet from 1938 through 1964, during which nuances related to course layout and scoring were refined by MSU coaches. As the 1970s progressed, its men’s cross country fortunes began to wane, perhaps in testament to the classic statistical maxim “regression to the mean,” but attributable to economic conditions and personnel decisions as well. Coincidentally, Michigan State opted to take a pioneering role in intercollegiate women’s athletics immediately preceding passage of Title IX legislation in 1972 and prior to its official implementation date in January 1975. Perhaps most notable was its hiring of Dr. Nell Jackson, Olympian and Olympic coach, as associate athletic director in1973. Cross country was not the first women’s sport recognized on campus, but MSU fielded one of the earlier university-sanctioned competitive teams in the United States in 1974. Dr. Jackson was a prominent advocate for women’s sport in general and took a lead role in budgetary deliberations and media relations. She initially served as Michigan State’s first women’s cross country coach before turning day-to-day operations to a distance running specialist, Mark Pittman, during that inaugural season. Michigan State won the first unofficial (1976) Big Ten women’s cross country championship and placed highly in AIAW and AAU competitions during its first eight seasons. Women’s cross country entered a new era in 1981 when both the Big Ten and NCAA staged their first competitions. MSU won the former and finished fourth in the latter. In addition to historic sources, including university archives and contemporary press coverage, primary sources for this paper include structured survey responses from over a dozen women and semi-structured interviews with five women and several coaches associated with Michigan State’s pioneering women’s cross country teams. Together, these materials provide in-depth perspective on a turbulent and foundational time with respect to women’s intercollegiate sport. Data suggest that challenges faced by early intercollegiate women runners were numerous. Coaches and administrators jockeyed internally and in the court of public opinion to carve an emerging niche. Athletes spoke of shared experience and social norms affecting women athletes, acceptance/ interaction with male athletes and the broader student population. Related themes included resistance and reinforcement of traditional gender roles, body image, and physicality of sport. Although Michigan State’s men’s team struggled during this time, evidence suggests that it would be a mistake to blame the men’s challenges on the fledgling women’s rise.

11. Havitz, M. E., Wilson, A. W., & Mock, S. E. (2012, October). Impact of Ego Involvement with Running on Varsity Athletes’ Post-University Running Participation and Health. Presented at the Sport Canada Research Initiative (SCRI) Conference, Ottawa, ON.